Universal Geneve Monodatic

By Ben Newport-Foster

Universal Geneve may have been the greatest watch manufacturer to stumble during the ‘quartz crisis’ and then lay dormant afterwards. Founded in 1894 by Numa Emile Descombes and Ulyesse George Perret, Universal Geneve created watches that captured the imagination of collectors and enthusiasts for over 100 hundred years. In 1917, they were among the first manufacturers to produce a wrist-worn chronograph and they continued making exquisite chronographs like the Compax, Bi-Compax and Tri-Compax throughout the 20th Century.

One of their classics was the Universal Geneve Polerouter. It is such an accomplishment in design that it almost overshadows every other dress watch made by the esteemed manufacturer. Whilst the Polerouter is deserving of its reputation, other dress watches made by Universal deserve your appreciation and the Monodatic is a great example of an under-appreciated classic.

Released in the early 1950s, the Monodatic is an example of a bygone era of watchmaking. The word 'timeless' is an often-used phrase when talking about watches (I've probably used it far more than advisable over the past few years), but I've come to appreciate designs that I call 'timeful'. The Monodatic is so 1950s that trying to compare it to modern designs is ultimately fruitless and I've found its best to sit back, take a long sip of an Old Fashioned, and bask it all in.

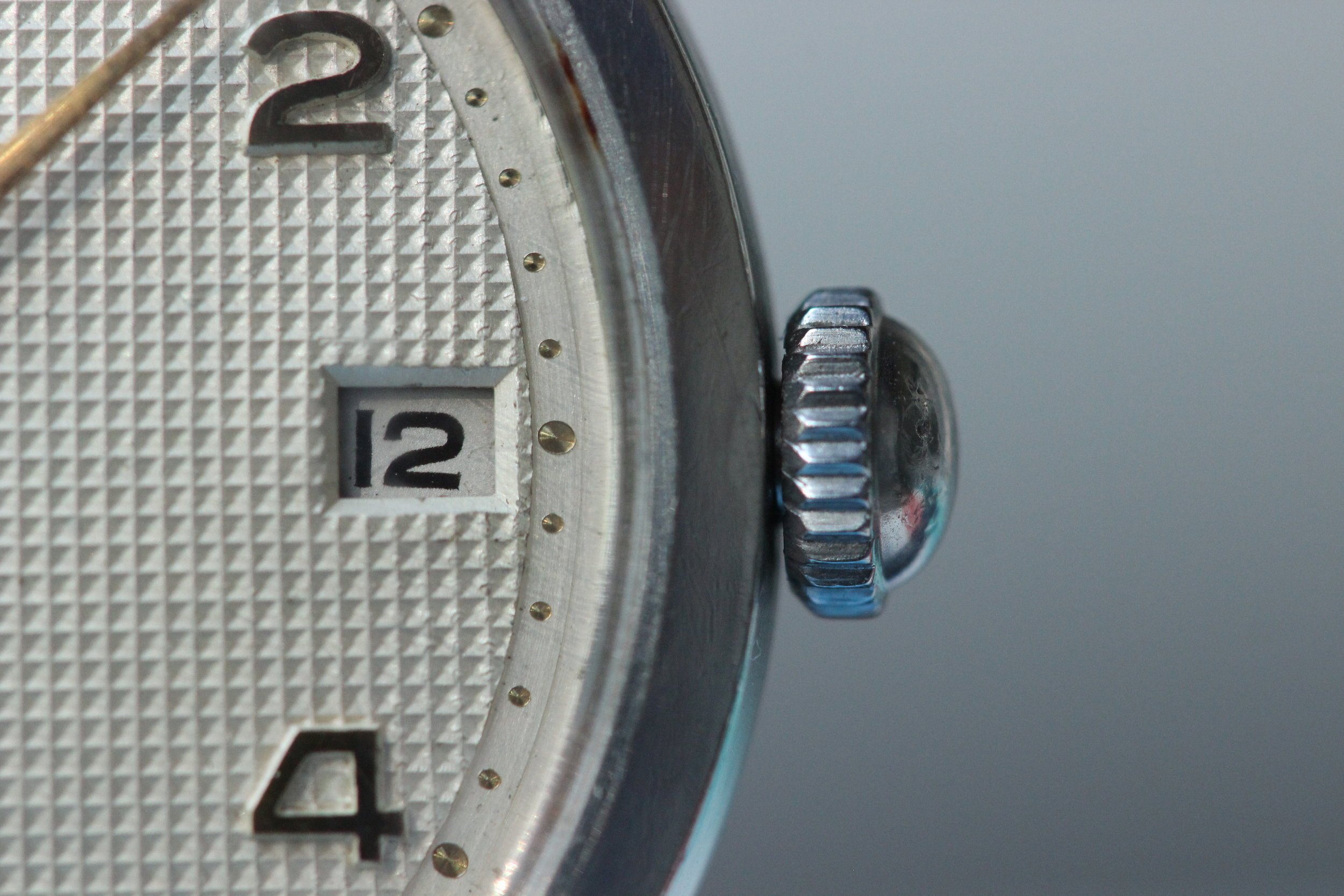

One of my favorite motifs of 1950s design is the roulette date wheel, a term for when the numbers on a date wheel alternate between red and black. It changes nothing about the functionality of the watch, but like the gold minute dots that surround the dial, it's just a charming, beautifully pointless addition. Another motif of 1950s watchmaking is a wider variety of dials and design within a particular reference. The Monodatic had a wide range of dials variations including matte black and silver, but the guilloche dial is by far the rarest and most beautiful of them all.

It's an extraordinarily simple watch, yet it has an astonishing level of detail that rewards repeated and attentive viewing. At arm's length, it looks like a simple cream dial but upon closer inspection, you see the beautiful honeycomb guilloche and the light playing across the narrow channels. You'll immediately notice the applied yellow gold markers, an even split between Arabic numbers and coffin shaped markers, but the subtle, raised centers of the coffins may pass you by on first glance.

The gold, dauphine hands have formed a delicious patina and contrast perfectly with the crisp, black ink that still clearly reads, even sixty-eight years later, Universal Geneve Monodatic. The most overlooked aspect of the watch, in my humble opinion, is easily going to be the small gold minute dots that surround the circumference of the dial, just outside the edge of the honeycomb finishing. They are such a small touch that you could easily overlook them, but they are a hallmark of a time in watchmaking when you got more for your money, not less.

Universal Geneve is famous for its pioneering use of the micro-rotor movement, a revolutionary (Please forgive the word play) style of movement that was revealed to the world in the Polerouter. Yet for many years, Universal Geneve had been making some excellent 'bumper' movements, like the Caliber 138.C.C seen on this watch. Like how a harpsichord is an ancestor to the piano, a bumper movement is the ancestor to the full automatic movement. Rather than have a large rotor rotate a complete 360 degrees to wind the main spring, a bumper rotor only has a partial rotation of 315 degrees. At the end of the travel, there are two buffer-springs placed on the end of the main plate. If you're paying attention whilst wearing the Monodatic, you'll feel the subtle bump of the rotor reaching its momentary resting point, before starting its journey again. Like the angled darts and the roulette date wheel, that ever-so-subtle knock you feel is a hallmark of a bygone era of watchmaking.